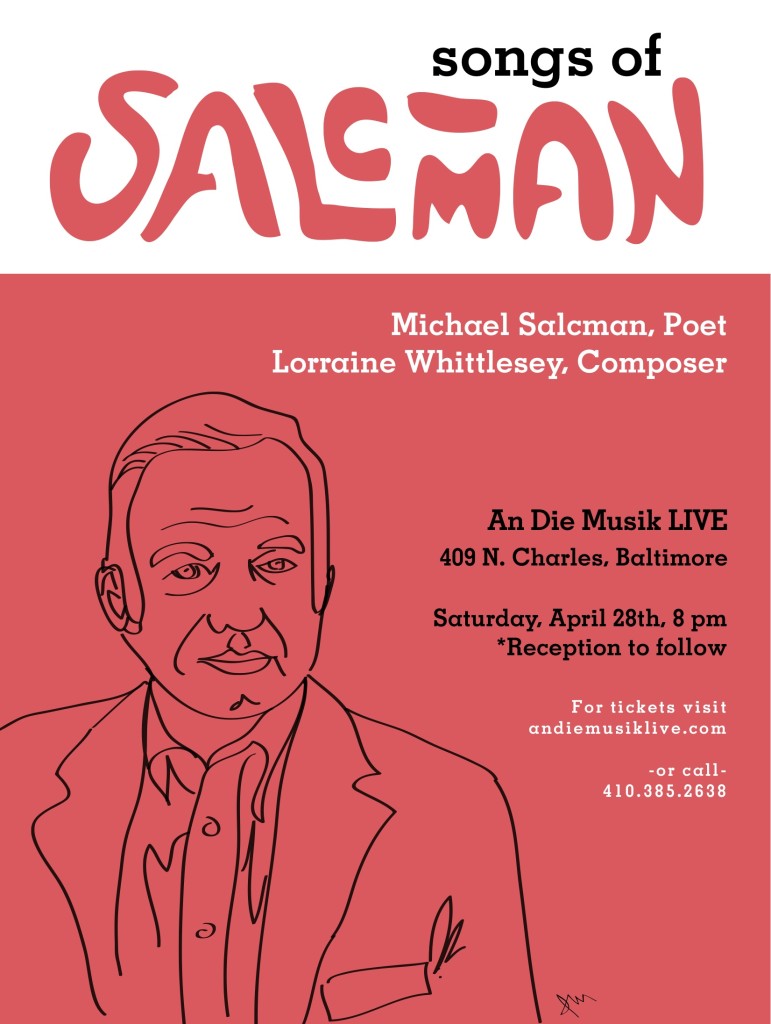

A FEW RANDOM THOUGHTS ABOUT THE ART SONG

Lorraine Whittlesey & Michael Salcman

at An die Musik, April 28, 2012

For those of you who missed last night’s evening at An die Musik in Baltimore, I thought I would share the introduction I read before the reading of the poems and Lorraine Whittlesey’s remarkable performance of her musical settings for “Einstein Sailing: A Photograph” (from The Clock Made of Confetti), “A Song of Spirals”, “Baltimore Was Always Blue”, “Poem on a Single Word from Richard Serra’s Verb List”, and “Everything But The Ashes” (all from The Enemy of Good Is Better), and the new poem “Song.” The performance was digitally recorded and we hope to have DVDs and CDs available in the near future.

The omens are good: this performance takes place in a hall named after one of the most famous Art Songs ever written, An die Musik by Franz Schubert (1817). I wish to briefly discuss some other lucky features about this evening, a notably happy event, hopefully for you and certainly for me because I am here to enjoy it and most distinguished composers who set poems to music, unlike Lorraine, have used texts by Dead poets. In the twentieth century examples include Copland’s 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson, Kurt Weill’s Four Walt Whitman Songs and the wide variety of deceased American and European poets found in the 129 Songs by Charles Ives. More recently (2008), Peter Lieberson used poems by Pablo Neruda to produce a beautiful set of love songs for his wife, the distinguished mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson; Neruda too was long gone. Using the words of a dead poet has obvious advantages for the composer and almost none for the poet. The original intent of the poet and the tone of the poem can be ignored when the poet is not around to object. Conflict may arise because poems are meant to be read aloud; in fact, a poem properly laid out on the page should function like a musical score, instructing the reader how best to perform the poem, where the breaths are taken, what the points of emphasis are and how long the pauses should be. These properties of the poem are potentially competitive with the musical setting but a member of the Dead Poets Society can hardly object to the treatment his poem receives at the hands of an inattentive reader or composer. As you will hear for yourself, this has not been my experience with Lorraine, whose attentiveness to my words and my intentions is beyond compare. Not being dead I have had the pleasure of seeing her at work and tonight am delighted to participate in the launch. In fact I would imagine there have been very few instances in which the premiere of a new cycle of Art Songs was presented by both the poet and the composer.

This brings me to my next point. One of the ways in which poems achieve their own afterlife is the attention of a distinguished composer. There are too many poets in the world, too few readers of poetry and precious few composers like Lorraine. We tend to think of the nineteenth century as the high-water mark of the Art Song but its most famous practitioners, Schubert, Schumann and Hugo Wolf, often used texts by German poets who are not much read today. Of course Schubert could set a bill of fare or a restaurant check to music. These composers liked the repetitive rhymes, insistent rhythms or meters, and syrupy Romanticism of the poetry they used, all of which served their compositional ease. As you will hear, Lorraine has not chosen the easy way; she has selected poems written in a wide range of forms that cover a number of complex and painful subjects; at all times, her seriousness of purpose has felt like a badge of honor. She’s been faithful to the pitch and rhythm with which the poems are read aloud, at least by me; her working methods feel familiar to any poet who writes poems that attempt true metaphoric justice to a painting or sculptural object. It seems to me that such ekphrastic poems bear the same relation to visual art that the Art Song bears to poetry; the Art Song shares the musicality of poetry and the poem shares with paintings the central importance of images. The difficulty in each case is the marriage of a shared property with due honor to both parties and their ineluctable differences. The goal is mutual enrichment. Lorraine and I hope you will enjoy this joint presentation of how text can be amplified by music.